Bohuslav Martinů Quartet for oboe and piano trio (1947)

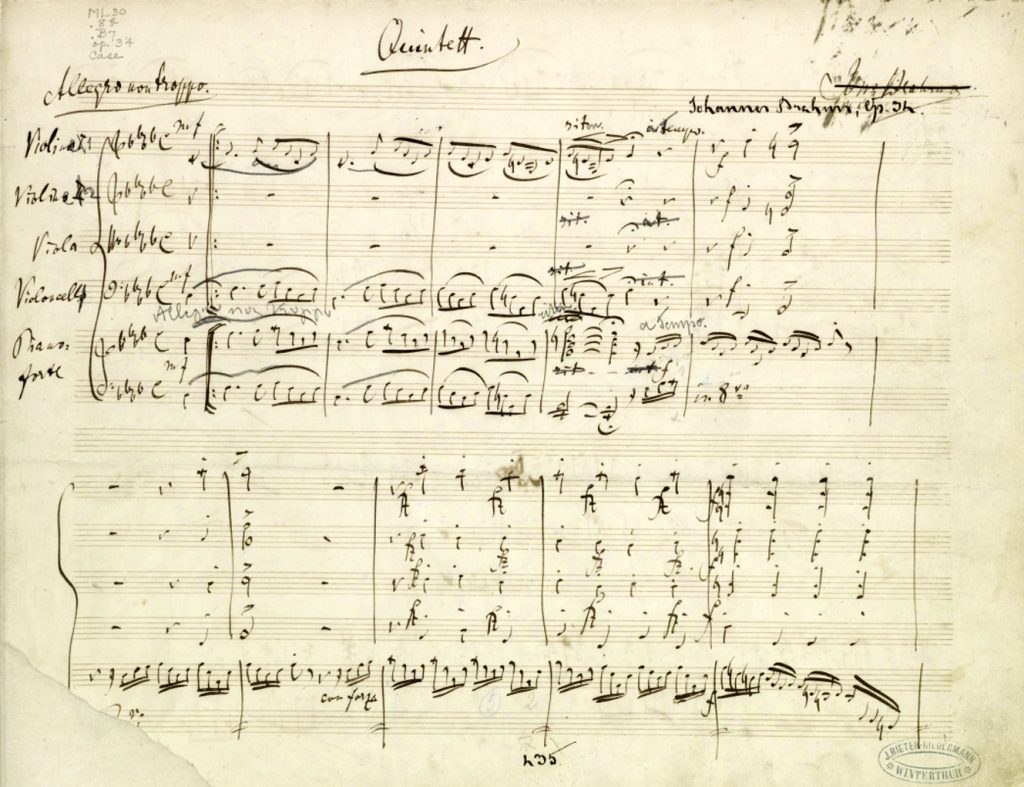

Johannes Brahms Piano Quintet in F minor, Op. 34 (1865)

Our third Jordan Hall concert of BCMS Season 39 will also be our first evening in that honored place in well over a decade. The program, consisting of the two works listed above, places the much-loved Brahms Piano Quintet in response to an oddly scored, mid-career work by Bohuslav Martinů (1890-1959), that we are presenting on our series for the first time.

[Compared to Schumann, the great poet, powerful, inspired, whose every note is individual…] Brahms is an inferior spirit whose pickax has probed every nook of counterpoint and modern harmony… He is not a born musician; his inventiveness is always insignificant and imitative…I have conscientiously followed his chamber music work: It holds up because it is based on deep study, but as for invention, it is faltering, and one senses that here is a man who looks right and left for what he cannot find within himself. Furthermore, on the pretext of increasing the sonorities, he abuses unison writing unbearably…And lastly, the piano quintet: There is in the ensemble of this work an explosive quality which gives one the hope that the composer has definitely found his groove…

Édouard Lalo in a letter to Pablo de Sarasate, Paris, August 28, 1878

Clearly, there were times and places when our revered Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) was not held in as high esteem as he is here today. Even his severest critics admired the various movements of the piano quintet for their high drama, lyricism, biting wit, and growing impetuosity. They also heard in the quintet the masterful deployment of embedded motif conceived to evolve endless possibilities for unifying and supporting large works. Arnold Schoenberg was quick to label Brahms “the progressive” for showing him, through ‘continuing variation,’ the way to evolve his own technique for composing with twelve equal tones. When we are able to follow even on the surface how a new phrase or section grows out of the literal or altered repetition of the conclusion of the previous phrase, we are hearing ‘continuing variation’ in action.

There are at least two good reasons for pairing Martinů’s Quartet for oboe and piano trio with Brahms’s Piano Quintet. First, the practice of ‘continuing variation’ is front and center in both works. Martinů’s music, seemingly in dialogue with itself, repeats new ideas among the players as in real conversation before morphing into the next topic. As in a good conversation we may overhear, each idea is repeated, feels heard and confirmed as it organically becomes the germ of the next musical idea.

And second, our global experience of most great tonal chamber music is in its beginning and ending in a home key. Martinů’s Quartet, not specifically in a key, centers on the key of F at its opening, and ends its final movement very strongly in C, which can seem incomplete, unresolved or, in this case, introductory to the Brahms which both begins and ends in F minor.

The Czech composer Bohuslav Martinů, like several other European musical exiles fleeing War in Europe, had tried settling in the United States. His name is often mentioned alongside Smetana, Dvořák, and Janáček as exponents and guardians of Moravian culture. He arrived in 1941, moving between New York and various New England locations until 1946. After the war he was hoping to assume a professorship at the Prague Conservatory, but was prevented from returning by the communists. In summer 1947 he was engaged to teach at Tanglewood, the same year he wrote Quartet for oboe and piano trio. He was notably prolific if not innovative; a loner, influenced by the evocative colors of Debussy and Les Six, but keen to keep Czech national character and tunes present in his music.

Enjoy.

MT

Read thru the program notes several times. Could not believe the dismissal of Brahams as “an inferior spirit”! Could jealously have been at play, or simply that he stretched

the rules of accepted composition?

Very interesting and informative!