Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Violin Sonata in B-flat, K. 454 (1784)

Felix Mendelssohn Piano Quartet No. 2 in F minor, Op. 2 (1823)

Anton Bruckner String Quintet in F major, WAB 112 (1878-79)

Music must never offend the ear, but must please the listener, or, in other words, must never cease to be music.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

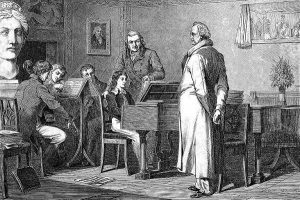

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Sonata for Piano and Violin K. 454 showed the highest development to date of the genre as the first (after many) in which he achieves a complete integration and balance between the two parts. It is reported that Mozart was sufficiently late in completing the work, perhaps due to many other commitments as composer and performer, that he took the extraordinary step of writing out the violin part for violinist Regina Strinasacchi to learn on her own, and performing the piano part at the premiere without prior rehearsal from a blank score. Haydn’s influence is evident in the structure of each movement starting with the slow introduction to the first. The slow movement contains surprises that still confuse and astonish listeners with unprecedented, breathtaking harmonic movement and satisfying resolution. This performance will be the first on the BCMS series.

There is so much talk about music, and yet so little is said. For my part I believe that words do not suffice, and if they did…I would have nothing more to do with music…The thoughts which are expressed to me by music that I love are not too indefinite to be put into words, but on the contrary, too definite.

Felix Mendelssohn

Born in 1809, Felix Mendelssohn came to the attention of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (Germany’s greatest poet) by age twelve, the same age at which Goethe himself first heard a seven-year-old named Mozart! Based on these extraordinary encounters that have linked their names in history, Goethe later assessed Mendelssohn to be the greater genius. However, Mendelssohn’s teacher, Carl Friedrich Zelter, seemed to understand that “many began like Mozart, but no one ever reached him.” Mendelssohn did manage to surpass Mozart in at least two respects—with more virtuosic piano writing in his three piano quartets. We recall from our last concert that seemingly unpopular virtuosic piano writing in Mozart’s first piano quartet caused the cancellation of the original contract for three by Hoffmeister, his publisher and fellow composer, and the delay in publication of the two finished quartets with a different publisher. While still in his early teenage years Mendelssohn was able to indulge the virtuosic and summon the sublime in his piano quartets, Sextet for Piano and Strings, and a year later at age sixteen in his Octet, which remains the greatest of all string octets since.

It is no common mortal who speaks to us in this music.

Anton Bruckner

Anton Bruckner’s two-viola quintet has been played by BCMS only once in our history, in 2001–far less frequently than any of Mozart’s six, Mendelssohn’s two (opening last season with his second); Brahms’s two (the first, published in 1883, the same year as Bruckner’s, and coming later this season); or Beethoven’s only, with which we opened this season! It is one of just two chamber works for string ensemble by a man known more for writing large masses and symphonies. Coming late in his output, between his sixth and seventh symphonies, it is most often compared in tone and formal design to these works and to the late Beethoven sting quartets which he did not know until after the quintet was completed. His practice of writing music deemed too long, too static, and lacking destination to resolution generated much criticism, many helpers and revisions that frustrate efforts by later performers to know the composer’s preference. In the time between composition, publication and first performance, the Scherzo was dropped and replaced with an Intermezzo thought more palatable to audiences. That change has since been rescinded and is observed in our performance.

As a self-declared Wagnerian, although very different, Bruckner is often mentioned in the same context with Mahler, who also wrote grand symphonies and very little chamber music. In our quintet Bruckner’s voice and language are scaled appropriately to the size of the ensemble, but reach for the sublime by going “beyond religious beliefs [of his Masses] to express the more fundamental, primitive stratum of feeling that gave these beliefs birth–a sense of the awe-inspiring, born of the naked wonder, fear and delight of elemental humanity confronted by the mysterious beauty and power of nature and the vast riddle of the cosmos.”

Enjoy.