Purchase / Stream options

Daniel Strong Godfrey: Ad Concordiam: Quintet Variations for Oboe, String Trio, and Piano (2018)

1. Inqueito / 4’19”

2. Lievemente / 6’15”

3. Scorrevole / 4’01”

4. Veloce / 5’22”

Peggy Pearson, oboe; Alyssa Wang, violin; Marcus Thompson, viola; Raman Ramakrishnan, cello; Max Levinson, piano

George Tsontakis: Portraits by El greco (Book I) for Clarinet, String Trio, and Piano (2014)

5. Toledo / 2’02”

6. Pietá / 5’22”

7. Christ and the Money Changers / 1’34”

8. The Vision / 5’20”

9. Christ Carrying the Cross / Entombment / 7’05”

10. Annunciation / 1’40”

Romie de Guise-Langlois, clarinet; Alyssa Wang, violin; Marcus Thompson, viola; Raman Ramakrishnan, cello; Max Levinson, piano

ELena Ruehr: Bächlein Helle, after Schubert, for Violin, Viola, cello, Double Bass, and Piano (2023)

11. ♩ = 120 / 5’41”

12. Senza misura – ♩ = 100 / 4’52”

13. Joyous ♩ = 100 / 4’42”

David Bowlin, violin; Marcus Thompson, viola; Raman Ramakrishnan, cello; Thomas Van Dyck, double bass; Max Levinson, piano

Total Time: 58’15”

Ad Concordiam: Quintet Variations for Oboe, String Trio, and Piano (2018)

Daniel Strong Godfrey (b. 1949)

Daniel Strong Godfrey is professor and chair of the Department of Music at Northeastern University’s College of Arts, Media and Design. He is founder and co-director of the Seal Bay Festival of American Chamber Music (Maine) and is co-author of Music Since 1945, published by Schirmer Books. Numerous awards and commissions include those from the J.S. Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Fromm Foundation, the Koussevitzky Music Foundation at the Library of Congress, and many others. Koch International Classics’ release of Godfrey’s String Quartet was named one of 2004’s best classical CDs by The New Yorker and The Rest is Noise. The principal players of the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra recorded seven of Godfrey’s chamber works in 2007 (Koch). Godfrey’s music has been performed by numerous orchestras and ensembles, including the Buffalo Philharmonic, Louisville Orchestra, Royal Philharmonic, Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, Collage New Music, VocalEssence, Da Capo Chamber Players, and numerous string quartets such as the Cassatt, Cuarteto Latinoamericano, Lark, and Portland.

Ad Concordiam was commissioned by the Boston Chamber Music Society and premiered on April 8, 2018 at Sanders Theatre. In his notes, Godfrey remarks upon the multiple meanings behind the title:

Ad Concordiam has overlapping meanings, as does its translation from the Latin: toward (in search of, in tribute to, aspiring to) harmony (or agreement, or unity, or…Concord). Having recently moved just next door to Concord, Massachusetts, and having frequented it often since attending high school nearby, I have always found it to be a central locus of my values and my sense of place. When it comes to values, Concord represents historically the ideals that motivated the formation of our union and that established, through the transcendentalists, a new standard for intellectual and moral integrity.

Even so, Godfrey emphasized that it was the values that Concord represented to him, more than the place itself, which seemed to capture his thoughts while composing the piece. The work’s subtitle is “Quintet Variations” and this aptly describes the four movements that are played without pause, as the material introduced at the beginning in the oboe, heard over tremolando strings, appears in various guises throughout the work. The music becomes increasingly motivic, and while the melody freely changes direction, there is an overall sense of build. The motivic responsibility transfers eventually to the violin, leading to a more energetic descending pizzicato line in the viola built upon these same motives, with the piano prancing alongside.

The violin’s melody eventually grows into a modal entreaty, only to somersault attacca into the Lietamente (“happily”) movement in 2/4. A syncopated melody in the oboe against the strings lends a playful whimsy, accentuated by the sparkling ascending scales. Godfrey distributes the lines across the instruments to vary both texture and expression. Energy and passion build, with moving passages in the middle voices, then come to rest in order to create space for an espressivo melody in the oboe, constructed with the same intervallic content as the opening motives. A wave once again builds then crests to introduce a new idea. The oboe offers a soulful and disjunct ballad and eventually there is a shimmering transition to playful syncopated dancing hemiola rhythms. The two ideas are cast together, ultimately reaching a sforzando dissonant chord in the piano. An arpeggiated flourish in the piano acts as a springboard for the oboe that muses briefly against open strings, before stretching into a soulful solo. The violin recalls the opening motivic material against sustained chords in the piano, and the keyboard, viola, and cello quietly move the piece into the ensuing movement.

The Scorrevole (“sliding,” “flowing”) movement opens with muted strings that murmur underneath a soaring melody in the violin, dissolving eventually into the murmuring gesture in the viola. The murmur is then transferred to the piano underneath a duet between violin and oboe. The texture grows more complex, as broken groupings in the cello and violin come to rest momentarily on a fermata. The viola recalls the pensive nature that the oboe introduced, this time in dialogue with the piano.

The strings gather forces to sweep powerfully into the Veloce movement. The oboe features an angular melody, punctuated by the piano and strings, that grows increasingly adamant, finally giving over to pizzicato and agitated strings in a quasi-fugue. Ultimately the piano reveals a clear statement of the theme, and what ensues is a revisiting of all the different characters from cantabile balladry to jaunty syncopation. The oboe reaches into its heights, vying for space in the chaotic texture until a trill in the cello signals a return to the original tempo. The ensemble seems to rally its forces through a whirlwind of syncopated energy that, like a cyclone, wraps everyone into the tempest until a final frenzied rush ends the maelstrom.

Portraits by El Greco (Book I): Quintet for Clarinet, Violin, Viola, Cello, and Piano (2014)

George Tsontakis (b. 1951)

George Tsontakis serves as Distinguished Composer in Residence at Bard College Conservatory of Music. He has received numerous awards including the coveted Grawemeyer Award for his Second Violin Concerto and the 2007 Ives Living Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He is artist-faculty emeritus with the Aspen Music Festival, where he was founding director of the Aspen Contemporary Ensemble in the 1990s. He has twice been selected for Kennedy Center Awards, received the lifetime achievement award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1995, and his Second Violin Concerto and Ghost Variations were both nominated for Grammy awards. Born in Astoria, New York into a family of strong Cretan heritage, he has become an increasingly important figure in the music of Greece. In 2021, Tsontakis composed a second set of Portraits by El Greco, co-commissioned by the Schubert Club, Festival Mosaic, Colorado College Chamber Music Festival, Arizona Friends of Music, and the Hellenic-American Cultural Foundation.

Portraits by El Greco (Book I) was commissioned in 2014 by the Boston Chamber Music Society for its 30th anniversary season and premiered on April 13, 2014 at Sanders Theatre. Artist Domenikos Theotokópoulous (1541–1614), better known as El Greco, is one of the best known Mannerist painters, with his 1586 The Burial of Count Orgaz for the Chapel of Santo Tomé in Toledo, Spain being the quintessential example. El Greco arrived in Venice sometime after 1560, wherein he would have studied the work of Titian, Jacopo Tintoretto and others, before being exposed a decade later to Raphael, Michelangelo, and Italian Mannerists in Rome. While his full name reflects his birthplace in Crete, Theotokópoulous went to Spain in the latter 1570s and lived there for the rest of his life. At the time, Toledo was heavily invested in the Counter-Reformation, but as H.W. Janson observed, El Greco’s “mature work was primarily a response to mysticism.” Indeed, many of the portraits referenced in this piece by George Tsontakis exploit the great emotional impact of Mannerist virtuosity in images, while expressing “his peculiar religiosity” that Janson likens to the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola, founder of the Jesuits, who “sought to make visions so real that they would seem to appear before the very eyes of the faithful.” George Tsontakis notes he was drawn to Theotokópoulous in part due to their shared connections to Crete (Tsontakis’s family is from Chania and Sfakia, Crete), and that he selected the paintings and composed with “‘all’ of [El Greco’s] works in my studied imagination and the [musical] impulses found their way to each painting.”

The dating of El Greco’s famous painting View of Toledo (fig. 1) is debated, but most sources place its creation between 1599 and 1600. While it is the only painting referenced in Tsontakis’s work that is not connected to the life of Christ, Toledo was, at the end of the sixteenth century, a religious epicenter in Spain. The painting is one of two surviving landscapes painted by El Greco, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (where it is held) notes that it is an “emotive rather than a documentary vision.” Tsontakis’s movement opens with the marking “Eerie and sublime solitude” which is evident in the painting from the overbearing sky and the city of Toledo far in the distance. The oscillating thirds are interspersed with glissandi (described as “silky” by the composer) in all instruments. Ascending arpeggiations in the piano against the austere oscillations in the violin and clarinet follow, and the cello and viola fill in the texture. The focus on timbre and articulation parallels El Greco’s aims with color and gesture. In some sense, Toledo provides both a backdrop for and a prelude to the movements that follow.

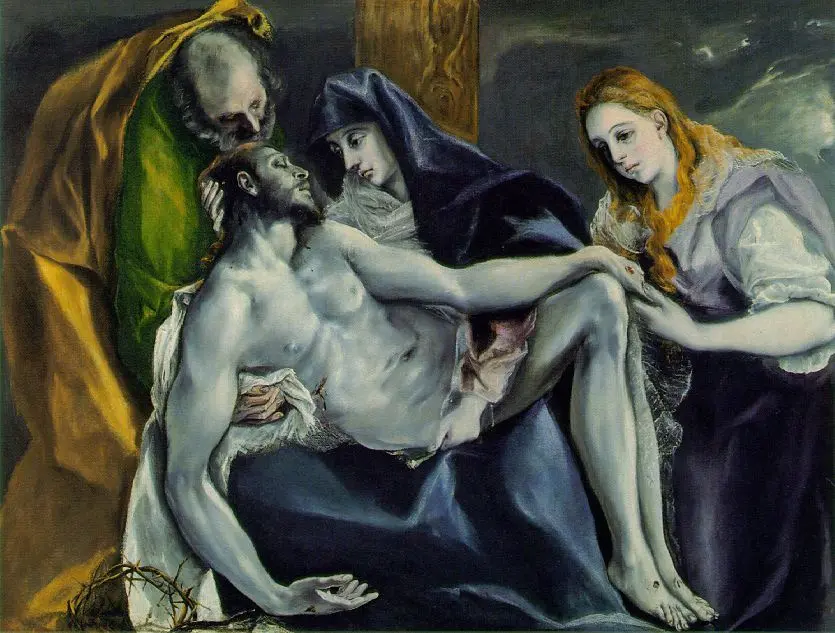

The second movement references El Greco’s Pietà (Mater Dolorosa) from c. 1592 (fig. 2). Mary mourning the death of Christ was one of the most iconic images in Renaissance art, and El Greco painted it more than once. This particular painting contrasts the bold colors of the living persons surrounding the pale blue-white body of Christ. While a truly mournful scene, El Greco also captures a sense of embrace with Mary cradling Jesus’s head, Saint Mary Magdalene gently holding his hand, and even Jesus’s front arm is curled softly suggesting his sacrifice’s embrace of humanity in Christian theology. The movement opens with a remarkable effect achieved by Tsontakis wherein the violin has similar gestures to the clarinet, but with a rhythm that puts it a fraction of a beat behind, creating a harmonic umbra rather than an echo. Gentle extended techniques, including scraping, are employed as well as vocalized, chanted “eh” syllables. An upward ascent with more pronounced fifths in the piano and harmonics in the cello recall Messiaen’s spiritual work Quartet for the End of Time. Tsontakis offers an “otherworldly (hypnotic) coda,” bringing back the idea of oscillating thirds from the first movement.

According to the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., the image of Christ cleansing the temple was strongly promoted iconography in the zeitgeist of the Council of Trent, which saw its Counter-Reformation aims as very much in keeping with purifying the Church of all things lascivious and impure. Painted sometime prior to 1570, Christ Cleansing the Temple (fig. 3) is a fascinating work that demonstrates El Greco’s ability to create movement, as Christ “spirals” through the center of the crowd, a scourge in his hand, ready to strike. The painter also incorporates motifs uncommonly used or not mentioned in the Bible, and in among the chaos there are nuanced interactions between members of the crowd. Jonathan Brown and Richard Mann offer, “Entreaty and Expulsion signify the gentle and severe means available to the Church for combatting sin.” Tsontakis channels Christ’s anger and a sense of expulsion in “Christ and the Money Changers” with the harsh tone of the clarinet, and a focus on gesture and articulation, including scraping the strings of the piano, and Bartók (snap) pizzicato. In several places in the work, Tsontakis employs a heavy use of the sustain pedal and here it serves to create a sense of the cavernous temple, complete with “grotesque bells” in the clarinet.

The Vision of St. John (fig. 4) is a particularly expressive and later work by El Greco—reportedly an inspiration for Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon—that references the apocalyptic moment in Revelations 6:9–11, when the fifth seal is broken, revealing the “souls of those who had been slaughtered for the word of God and for the testimony they had given” (NRSV). Here again, in “The Vision,” one initially catches reminiscences of Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time—particularly the “Dance of Fury” movement, both in terms of accentuation and homorhythmic texture—but it is soon displaced by a pattern of couplets with staccato eighth note punctuations in the piano. Much like mystical visions described in several sources, the movement spins into tremolando brilliance with ecstatic and emphatic chords in the piano. The piano seems insistent and unceasing, but finally gives way to an ethereal line in the clarinet, supported by muted strings. A “reedy” crescendo in the clarinet signals a section marked “fiercely tolling bells” that carries the energy of the early piano chords, but now across the quintet. The tumult vaporizes and a barely audible tremolo halo in the clarinet materializes over gentle chords in the piano, and the strings join the celestial shimmer that becomes its own soundscape. A rising fourth motive in the clarinet leaves an unanswered question as the final chords of the piano fade into silence.

As described by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, El Greco’s Christ Carrying the Cross (fig. 5) is notable as a “devotional image of haunting immediacy and resonant with pathos” rather than a narrative scene. One is struck by the way Christ carries the cross leaning against his shoulder, his eyes cast upwards toward heaven as he ascends the hill. Here Tsontakis directs that the movement opens “Mysteriously, like distant handbells, inwardly and intensely ‘controlled.’” The composer’s use of 5/8 and 2/4 alternating passages offers a sense of cantus firmus. As in the second movement, a chanted “eh” returns, this time in the guise of a medieval organum in a sustained fifth. The clarinet’s melody is increasingly plaintive, in slower quarter notes. The movement shifts to “Entombment” cast as a quasi-chorale in the strings and piano, which soon bursts out of solemnity and into passion, with weeping glissandi that pierce through the texture like nails, then overlapping into lachrymose solemnity. This captures both the color of the living that surround the body of Christ in El Greco’s painting (fig. 6), as well as the downcast eyes and burdened shoulders of embodied grief.

Tsontakis provides a postlude through reference to El Greco’s The Annunciation (fig. 7). Marked “A heartbeat, with wonder,” the piano provides the heartbeat, while the fluttering tremolandi in the violin and viola suggest the Holy Spirit, cast as a dove in the painting, that flies between Mary and the archangel Gabriel revealing the news that she will give birth to the Son of God.

Bächlein Helle, after Schubert, for Violin, Viola, Cello, Bass, and Piano (2024)

Elena Ruehr (b. 1963)

Elena Ruehr’s accolades and awards are many, including Guggenheim and Harvard Radcliffe fellowships, and residencies with the Boston Modern Orchestra Project and Lincoln’s Symphony Orchestra. She studied with William Bolcom at University of Michigan, as well as with Vincent Persichetti and Bernard Rands at Juilliard. Her oeuvre includes many works for voice, including five operas and five cantatas, as well as pieces for orchestra, wind ensemble, dance, and silent film. She has been commissioned and recorded by numerous string quartets, including the Arneis, Cypress, Borromeo, Lark, Quartet Nouveau, and Shanghai String Quartets. In addition to composition, Ruehr has also studied modern dance and has played in Javanese and West African performing ensembles. She has taught at MIT since 1992, where she won the Baker Undergraduate Teaching Award.

Ruehr’s Bächlein Helle, after Schubert was commissioned by the Boston Chamber Music Society and premiered on February 25, 2024 at Sanders Theatre. It takes as its inspiration both the text, written by Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart, of Franz Schubert’s Lied “Die Forelle” (The Trout) as well that composer’s well-known Piano Quintet in A major, D. 667 (aka the Trout Quintet), written for the same ensemble of piano, violin, viola, cello and double bass. The opening line of the Lied is “In einem Bächlein helle” (In a clear little brook), and certainly there is much in Ruehr’s piece that captures the essence of a bubbling stream. But as the composer reveals, there is a deeper connection, both in the set of pitches Ruehr uses as the primary basis for the piece: A C C# E F—drawn from both A major and F major triads, significant to the Trout Quintet—and also a deeper metaphorical connection to the song. The composer states:

Although Schubert and Schubart’s metaphor had a different meaning at the time, to me it is an interesting metaphor about modern life: we are all consumers, but we are conflicted about our consumption and how it challenges the natural world we live in. This conflict is expressed through the conflict of the harmonic source material I chose. The piece begins with conflict, but ends with acceptance.

Indeed, from the outset, and throughout the piece, both the illumination (and sometimes juxtaposition) of all these components is clear. The first movement opens with oscillating sixteenth notes in the violin, against an ostinato pattern of eighth notes in the viola, which taken together comprise Ruehr’s pitch set referenced above. The piano’s harmonies match up with the viola, but are displaced, creating a quiet tension. The strings take up the forward movement as the babbling Bächlein moves into the piano. A “heroic” theme (as marked in the score) heralded by a rising fifth, is passed with alterations from viola to violin to cello before the viola and violin settle into “spooky” (again, as marked in the score) patterns above pizzicato in the cello, while the piano carries the theme. Ruehr offers seamless shifts of melodic and accompanimental responsibilities between the instruments. The movement features chromatic motion that is always forward moving, never static, but also plaintive melodies that stretch and reframe the emotional underpinnings. The piano is like an underground spring that surges forth sometimes unexpectedly, moving the current of the piece ever forward. The rising motive of the heroic melody is recalled to become a cadential figure drawing the first movement to a close on an open ending that leaves chromatic tension in the air.

The second movement opens with brief and mysterious utterance in the piano before a gentle rocking third in the viola supports an ascending melody in the violin, hearkening back to a more Schubertian guise. The homophonic classicism of the strings offers a restful lyricism before the piano enters again with its mystery. The cello and piano then play a duet, softly punctuated by pizzicato. The lyricism is juxtaposed with another moment of increased dissonance before returning to the melodious musings. Ruehr switches to triple meter with a viola melody marked “a little off kilter” that sits just on the edge of consonance until it dissolves into a dissonant—almost whispered—cluster that transitions to a final understated pizzicato passage in the double bass as the movement floats away.

Homophonic and celebratory cascades mark the festive opening to the finale, with its playfully triadic gestures. Ruehr then provides two harmonic groupings: one between violin, viola, and cello, and the other a pairing of the bass with the piano, ultimately landing in a surprising 5/8. “Ferocious” gestures and a sense of urgency supplant the joy, and here again Ruehr plays with momentum and stasis, consonance and dissonance, providing the space to thoughtfully consider conflict—arguably necessary to reach the final notes of joyous acceptance.

© 2024 Rebecca G. Marchand

Our Art in Our Time

Founded by BCMS Artistic Director Marcus Thompson to “actively contribute to the creation of our art in our time,” the BCMS Commissioning Club sustains the historic practice through which the gift of great music is passed to future generations.

Since 2014, one new work has been featured on BCMS’s concert series each season. Many of them, written in response to previous masterpieces, have been heard on other chamber series, inspiring sequels and positive responses.

In honor of its 40th anniversary season in 2022-2023, BCMS committed to professionally capturing the premiere and reprise live concert recording of its commissions through 2025, further fulfilling its mission to make the chamber music artform more accessible to all.

… [Tsontakis’s] Book 1 of Portraits by El Greco are no mere impressions of paint and canvas. Rather, they relay a palpable emotional gravity, even Messiaenic mystery…. [The work] explores energy and subtlety through the sparsest of textures and gestures.

The Boston Musical Intelligencer

We wish to express special gratitude to the sponsors of this recording project. Without each of these patrons the project would not be possible.

Constantine Alexander and Linda Reinfeld • Jeffrey S. Berman and Jan Walker • Anselm C. Blumer and Dorothy C. Buck • Pamela and Lee Bromberg • Cynthia A. Clark and Willard McGraw • Marjorie B. and Martin Cohn • David Friend and Margaret Shepherd • John and Ellen Harris • Tom and Kate Kush • Marc Maxwell • Donald and Marilyn Malpass • The estate of Dr. Irene A. Nichols • The Theodore and Jane Norman Fund for Faculty Research and Creative Projects of Brandeis University • Bill and Kathleen Rousseau • Steven and Susan Sewall • Ellen and Jay Sklar

Recorded on October 15, 2023 (Godfrey) and February 25, 2024 (Ruehr) at Harvard University’s Sanders Theatre, Cambridge, MA; and January 21, 2024 (Tsontakis) at New England Conservatory’s Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Cover photo: The North Bridge in Concord, Massachusetts. It is often referred to as the location of the “shot heard round the world,” and the beginning of the American War for Independence.

Producer: Marcus Thompson

Recording engineer: Antonio Oliart Ros

Score readers and assistant editors: Heather Braun (Godfrey, Ruehr), Jeffrey Means (Tsontakis)

Design and production manager: Wen Huang

Project assistant: Melany Piech